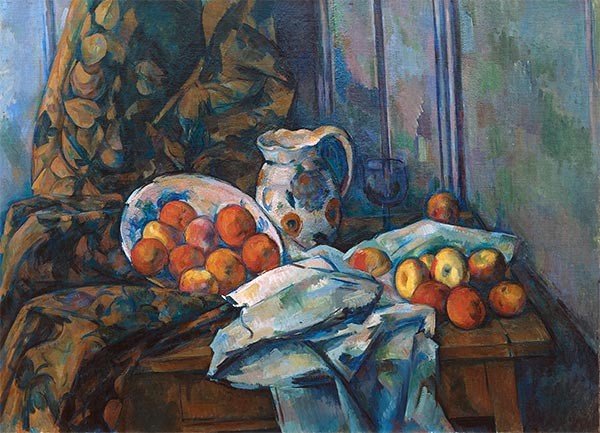

Still life with milk jug and fruit FWN 878 1900 45.8cm x 54.9 Washington

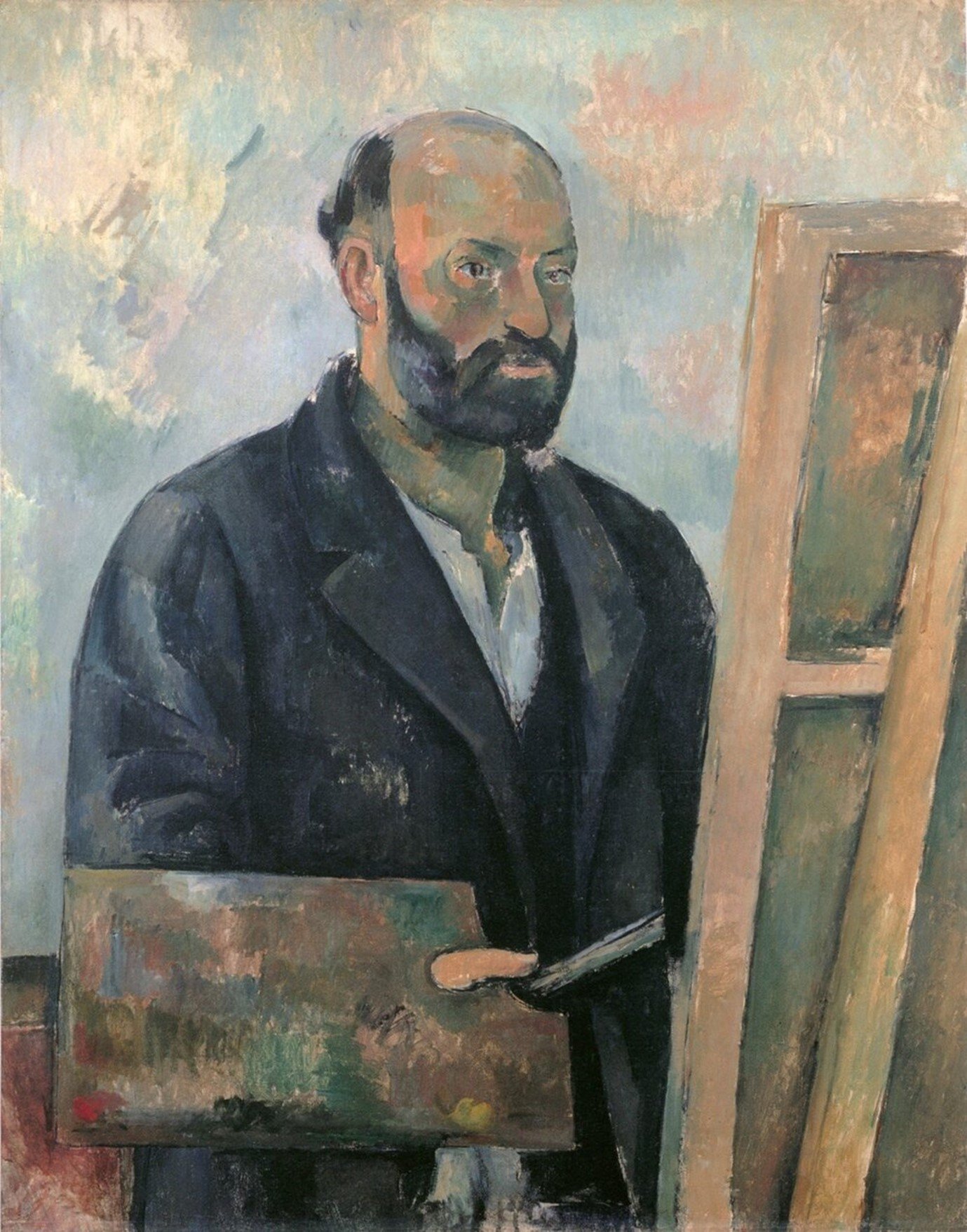

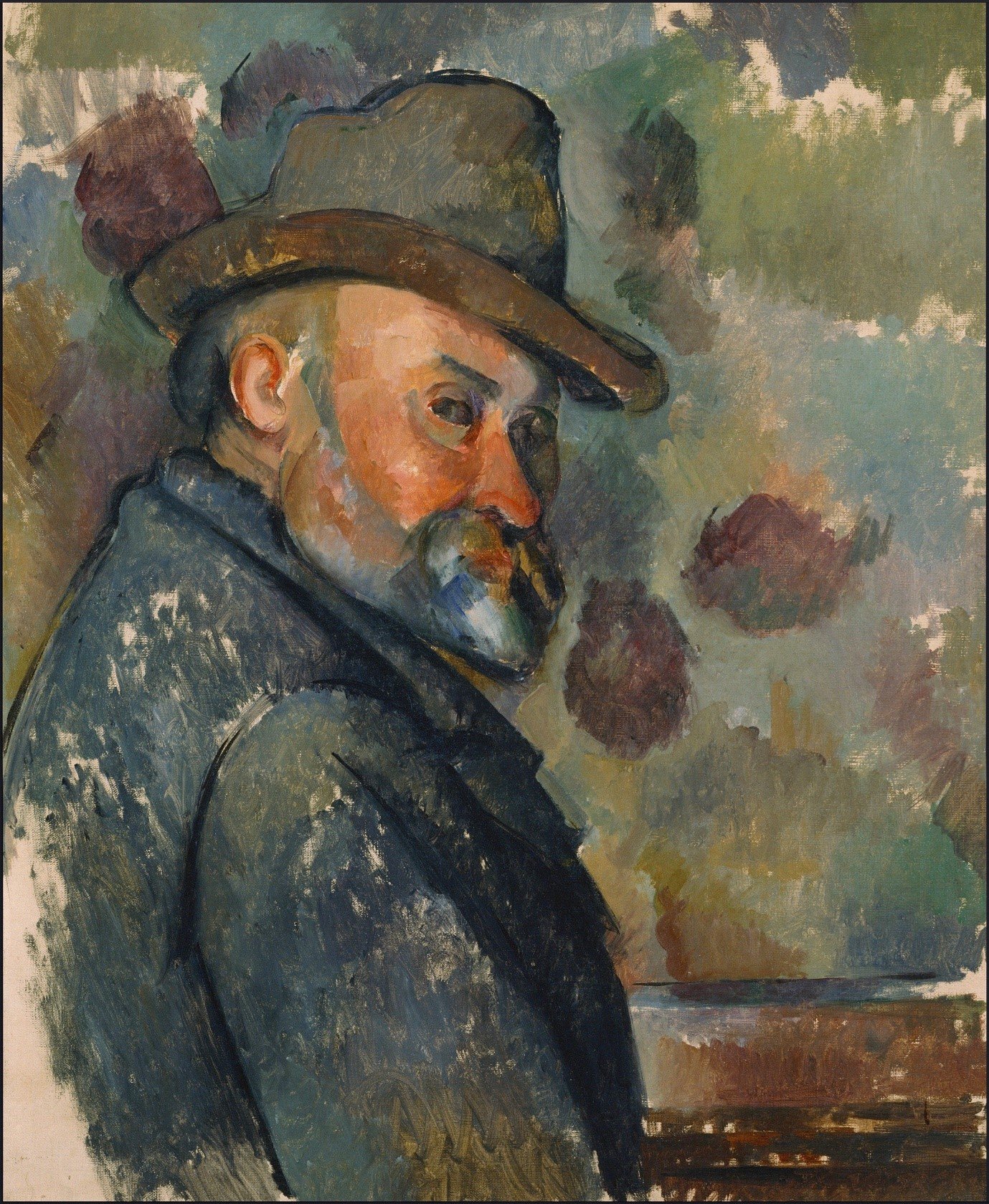

In this short series of blogs, I will look at three of Cezanne’s paintings of Apples from around the turn of the century, 1900, just as he turned 60 years of age. Spending more and more time in Aix rather than Paris, he became a kind of rural myth, and began to attract young writers and would-be artists who heard of him through the admiration of artists living in Paris, and because he had been the school-mate and soul-friend of the now notorious anti-establishment critic, Zola. And - who’d have thought it – he was receiving his young admirers graciously! I hope you enjoy the last of the three blogs….

“Blessed are they who see beautiful things in humble places where other people see nothing.” Pissarro

The more I look at this painting, the more I love it! I try simply to behold it in its fulness and in its simplicity. If my mind tries to alight on one specific feature, then I gently say: “not yet”, and return to my beholding. My intention is to behold the whole, without thought or analysis, distinction or distraction; just with focus and openness, joy and gratitude. In this way, I can approach its fulness and its simplicity at once; for in this meditative practice, fulness and simplicity are not two separate entities but one. I begin to behold the whole.

It is the experience of the beholding of the whole that Cezanne discovers at the heart of his practice of painting in the last fifteen years of his life and work, though he had no words to express it. Fortunately for us, we live in an era when the experience of the beholding of the whole is one of its defining features; and so we can utilize that experience to understand more fully what was inspiring Cezanne.

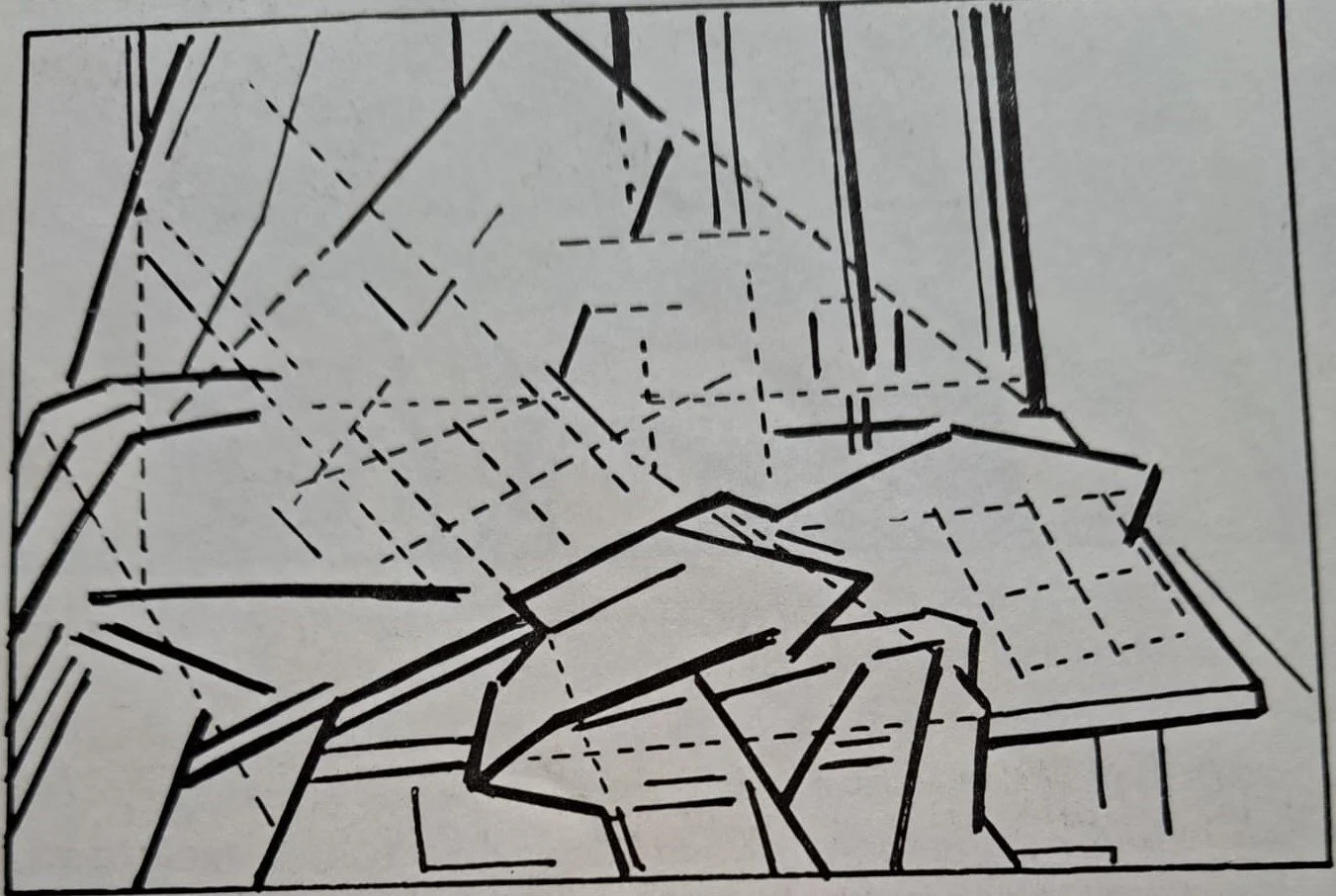

If you do not approach this painting in search of the whole, then all kinds of problems can crop up. Erle Loran, in his brilliant analysis of Cezanne’s composition published in 1943, entitles one chapter: ‘The problem of Cezanne’s bent tables’, and goes on to ‘prove’ that Cezanne bent his tables intentionally, because elsewhere, Cezanne did paint some dead-straight lines – so Cezanne could draw straight when he wanted to! John Rewald in his comprehensive and detailed catalogue of Cezanne’s works published in 1996 after a life of dedication to the task, comments that Cezanne’s ‘concentration on a specific section prevents him from straightening linear features’, having described it as ‘the badly aligned table’. Comments like these suggest that even the experts were not quite sure whether to describe these features of Cezanne’s work – precisely the features that the general public of the time found so wanting, and often, so annoying – as quirky Cezannean stuff or as the intentional practice of a Master. (There was talk in Cezanne’s lifetime of the possibility that Cezanne’s sight was defective, and later that his sight might have been affected by diabetes.)

If we ask what’s going on here, we do well to think about how society has developed. Loran and Rewald realized Cezanne’s genius, and explained it from within their understanding: a ‘Modernist’ world-view (one that Cezanne had himself co-created when he was an Impressionist painter). We saw in the first blog how our writers, T J Clark and C Armstrong, have since presented critical analysis of the ‘Modernist’ approach, in an attempt to ‘rescue’ Cezanne’s work by re-interpreting it from a different world-view.

Nina Maria Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, in a book of 2003, entitled Cezanne and Provence is not bothered about bent or badly aligned tables, but rather about ‘The painter in his culture’ (the subtitle of the book). Her understanding of Cezanne’s genius stems from her ‘Pluralist’ world-view, in which prominence is afforded to diversity – absolute truth is replaced by truth-fulness; the sum total of everybody’s truth. For Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, the genius of Cezanne lies in paintings where he views a motif from different viewpoints. The thesis of her book is rooted in Cezanne’s decision later in life to leave Paris and return to Provence, where he can imbibe once again the traditional culture of Provence. Athanassoglou-Kallmyer seeks thereby to re-balance our traditional understanding of French Culture away from Paris, towards Provence.

A new worldview is beginning to grow in our time: ‘Integral’. One of the most important elements of this burgeoning worldview is that of seeing ‘the whole’. We see this shift towards ‘beholding the whole’ in all kinds of disciplines – in traditional economics towards doughnut economics; from monoculture to bio-diversity and eco-systems; from thinking of individuals to institutions; even in physics, from atoms and elements to waves and relationships.

As a new worldview comes on stream, there is a linguistic gap: the language and the enshrined concepts of the old worldview do not fit the new; the new worldview has not yet developed a language and concepts of its own. In his book entitled ‘Cezanne, A Life’, Alex Danchev astutely writes: “Contrary to popular belief, it is given to artists, not politicians, to create a new world order”. In his translation of Cezanne’s letters, Danchev records the letter written by Cezanne in November 1889 to the secretary of the Belgium avant-garde group Les XX, in which Cezanne acknowledges: “I have resolved to work in silence, until the day when I should feel capable of defending theoretically the results of my endeavours”. Cezanne was never to achieve this; not because of his lack of intellectual prowess, but because he was ahead of his time, and painting out of a worldview that did not yet exist in words and concepts.

A generation later, the close colleague of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque did not have the ‘right’ words either to express Cezanne’s genius and names it as best he can as ‘a new moral intimation of space’. He says:

“The discovery of his work (Cezanne’s) overturned everything. I wasn’t alone in suffering from shock. There was a battle to be fought against much of what we knew, what we had tended to respect, admire or love. In Cezanne’s work, we should not only see a new pictorial construction but also – too often forgot – a new moral intimation of space” George Braque, 1882 to 1963

And maybe, one of those young admirers who Cezanne received so graciously in Aix, the Expressionist painter Charles Camoin, had it right: “From the novelty and the importance of his contribution Cezanne is a genius. He is one of those who determine evolution.” (1905)

An ‘Integral worldview’ provides a more comprehensive understanding of generative change and evolutionary transition, and, more pertinently here, of the complexity and simplicity of Cezanne’s Oeuvre.

For an introduction to ‘Integral’, have a look at the work of Ken Wilber and Integral Dynamics (not mathematical references). (for a quick intro you can go to Jeff Salzman’s Quick Intro to Integral Theory - The Daily Evolver)

The mind must set itself up wherever it goes,

and it would be most convenient to impose

its old rooms –

just tack them up like an interior tent.

Uh Oh!

But the new holes aren’t

where the windows went!

Kay Ryan