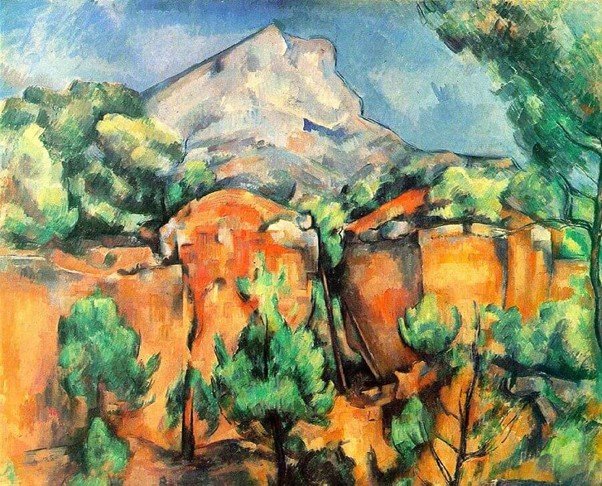

Mont Sainte Victoire seen from Bibemus FWN 315 65.1cm x 81.3 1897 Baltimore

This is the third post of the mini-series of four posts focusing on three paintings by Cezanne, all with the same motif – Bibemus Quarry – and all painted in a two-year period 1895-7, in Cezanne’s ‘mature phase’, when he was just a few years shy of 60. The first post focused on Cezanne’s painting ‘Bibemus’ FWN 305, in the style of Impressionism. This second post focuses on the painting called ‘Bibemus Quarry’ FWN 306. This third post focusing on Bibemus and Mont Sainte Victoire. For me, it is clear that these paintings represent Cezanne’s understanding of his own development; he now sees clearly the stages of his own growth, and expresses that development in the mode of communication in which he is most proficient – oil paint on canvass. The beauty of growth is that it is the expression of your deepest yearnings; the truth of growth is that it requires dissonance, pain and resolve; but the goodness of growth is that it lifts you beyond yourself to wider horizons. I hope you enjoy this mini-series.

Sometimes it can take a long time – years – to comprehend the full implications of our own development. It is so hard to resist the habitual residue of our old ways of understanding. Old polarities insinuate themselves into our thought processes. Family, friends and acquaintances transport us back to the good old days. We slip into easy choices between this and that. Our space is confined by polarities.

But maybe, our spaciousness does not have to be confined by polarities, confined as an example between the self and others, confined within our skin. We breathe the air’s oxygen and we exhale carbon dioxide; we are part of an ecosystem, ourselves an ecosystem within an ecosystem. A part of a whole, a whole within a part, and a whole within a whole.

The assimilation of this fractal understanding is I believe what Cezanne is struggling to express. It is the spiritual experience of wholeness that informs his mature stage of painting. This is what Cezanne is trying to express here as he stands within the ecosystem that encompasses Bibemus quarry and Montagne Saint Victoire: deep within, entangled in, the ochre molasse sandstone compressed into orange rock by the geological formation of the mountain Sainte Victoire, enfolded haptically in pigments and brushes, and the breeze of bushes and trees.

The birds have vanished from the sky;

now the last cloud floats away.

We sit together, the mountain and me,

until only the mountain remains.

Li Bai of the Tang Dynasty (adapted)

I believe Cezanne experienced this sense of wholeness, and it was this experience that underpinned his mature phase. The following is an exploration of ‘how’ he expresses his experience, using all the lessons, skills and techniques that he has acquired on his journey of development.

Firstly, ‘Scale’ is thoroughly flexible – ‘plasticity’; Cezanne does not abide by scientific perspective, but through the denial of polarities moves towards a complexity of harmony. Cezanne diminishes the foreground, and increases the background size of stuff – in the diagram 1, below, the shaded area, A, is the size that Mont Sainte Victoire appears in a photograph. (all diagrams and analysis is based on Erle Loran’s Cezanne’s Composition).

Cezanne avoids aerial perspective by excluding the fuzziness encountered when viewing something that is far away (Impressionist beauty), by defining quite clearly and intensely the outline of the mountain using bright blue stokes of paint. Cezanne tilts the background up out of depth so as to counteract any falling away within a traditional perspective. And finally, Cezanne scatters the fusing of different colourful planes to excite our viewing.

Secondly, by using the organizational techniques of pictorial composition (Cezanne’s ‘Constructivist Phase). This is illustrated by Loran’s second diagram below.

Open forms (without defined edges) are integrated by the overall circular movement of the painting. There are rhythmic flows created by overlapping and leaning plane on plane. In fact, Cezanne maintains a surprising resemblance to the motif, despite the freedom he enlists in expressing the intricacy of the forms.

Thirdly, Cezanne employs decorative features through-out. This is clearly expressed by Loran’s third diagram below, in which we can see how the shapes of the trees, (circular, flamelike, triangular, oval, and random) are scattered through-out.

Fourthly, Cezanne uses repetition of colours to link and align, (integrate) the dominant feature, the mountain, within the whole. The final Loran diagram shows how Cezanne reflects the colour of the mountain across the middle ground, and forefront of the painting.

And finally, Cezanne’s use of complementary colours, the colours of Provence. ‘The orange of the cliffs and earth is the most intense and dominant colour, covering over half the surface’; the green of the trees is less saturated, but more complex; the blue sky providing the cool contrast with the orange cliffs. The whitish, and dark purple of the mountain provides for its magnificence.

Modern day photo of Bibemus