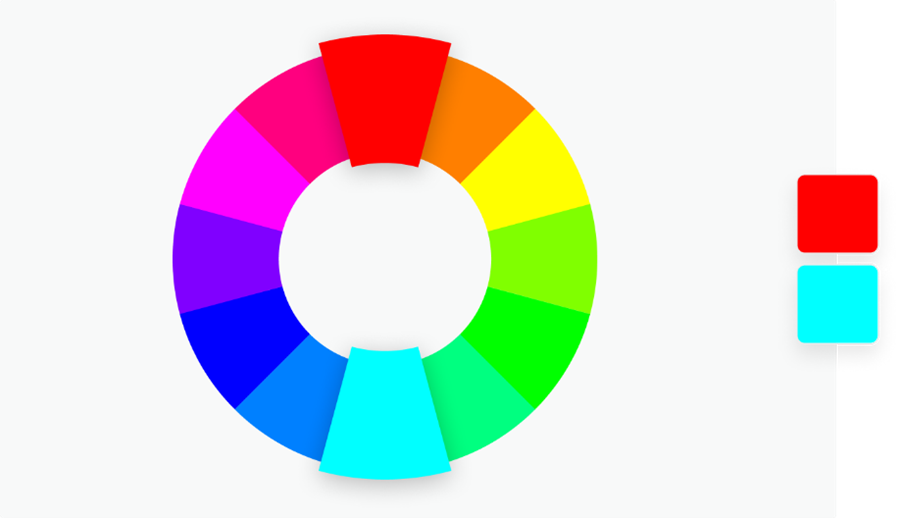

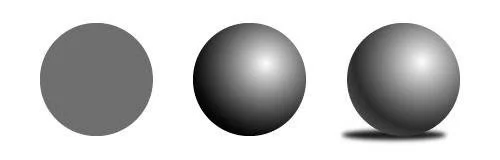

It is the change in value that gives us the ability to see objects as three-dimensional. In the illustration above, the circle on the left is a solid colour and appears flat. The lighter and darker areas of the circle in the middle give it dimension, and we see it as a sphere.

Value also guides our perception of space. The middle circle looks like it is floating in space. By darkening the colour below the shape, the same sphere appears to be sitting on a surface.

These three circles are all flat. It is the change in value that gives an impression of dimension. It is also the change in value that indicates where the object is within its environment.

We may not consciously be thinking about value, but when our eyes are open, our mind is continually making value comparisons all of the time.

High key colour describes the set of colours that range from mid-tone hues to white, while low key colour spans the range from mid-tone to black. (cf Sensationcolor)

(Human) Values (sometimes called ‘memes’): values are what motivate people to act in the way that they do. We develop values in response to our environment.

Value system: the collection of values that adhere together, that different groups of people tend to hold together, with a set of unique characteristics, qualities and shadows. There have been eight Value systems so far in the evolution of humankind.

It was often said that genes are to genetics and biology, what memes are to memetics and culture; but you can find a fuller understanding of the philosophical (epistemological) framework of ‘value-systems, at Overview Value Systems ⋅ Spiral Dynamics Integral

***************

The Blue Vase

It is the blue hue of the paint applied on canvass that vibrates the expansive and cool mood within us within which the blue vase floats without.

It is the expansive and cool mood within us and without, that brings us into harmony with the clear blue of sea and sky that is our openness to depth and transcendence.

It is our openness to depth and transcendence that centres the integrity of our being.

blue is cool.

This was the era when humanity turned up the heat.

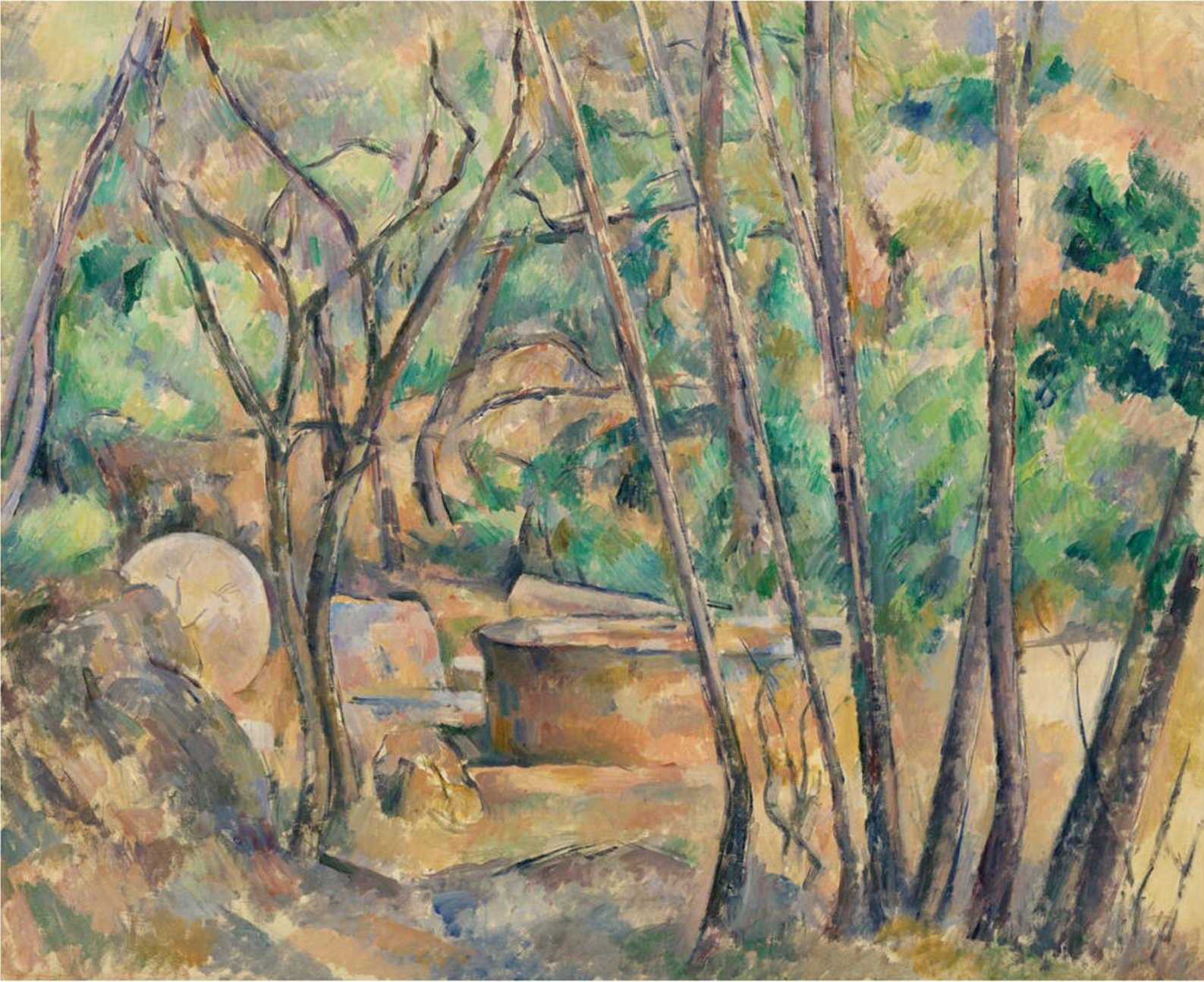

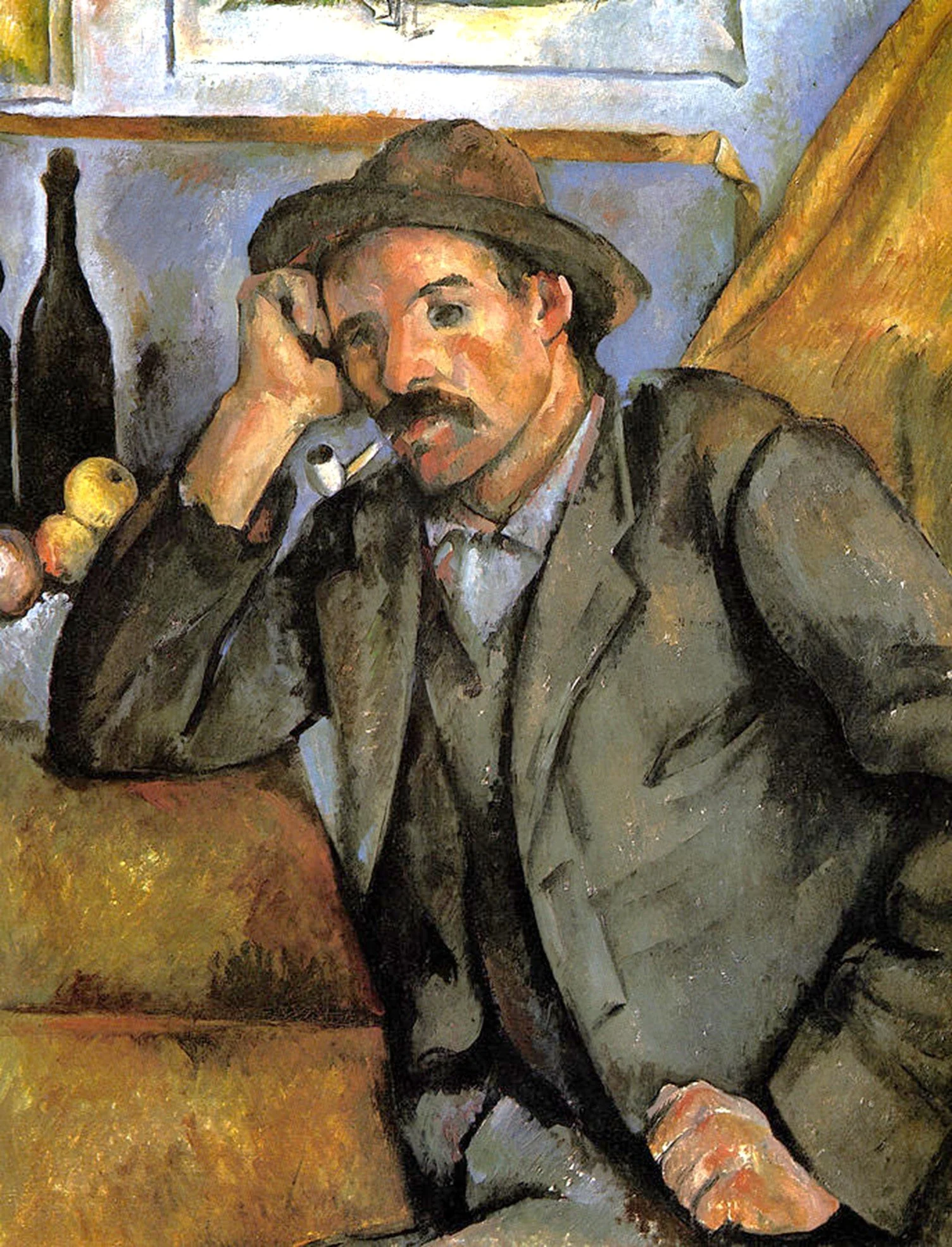

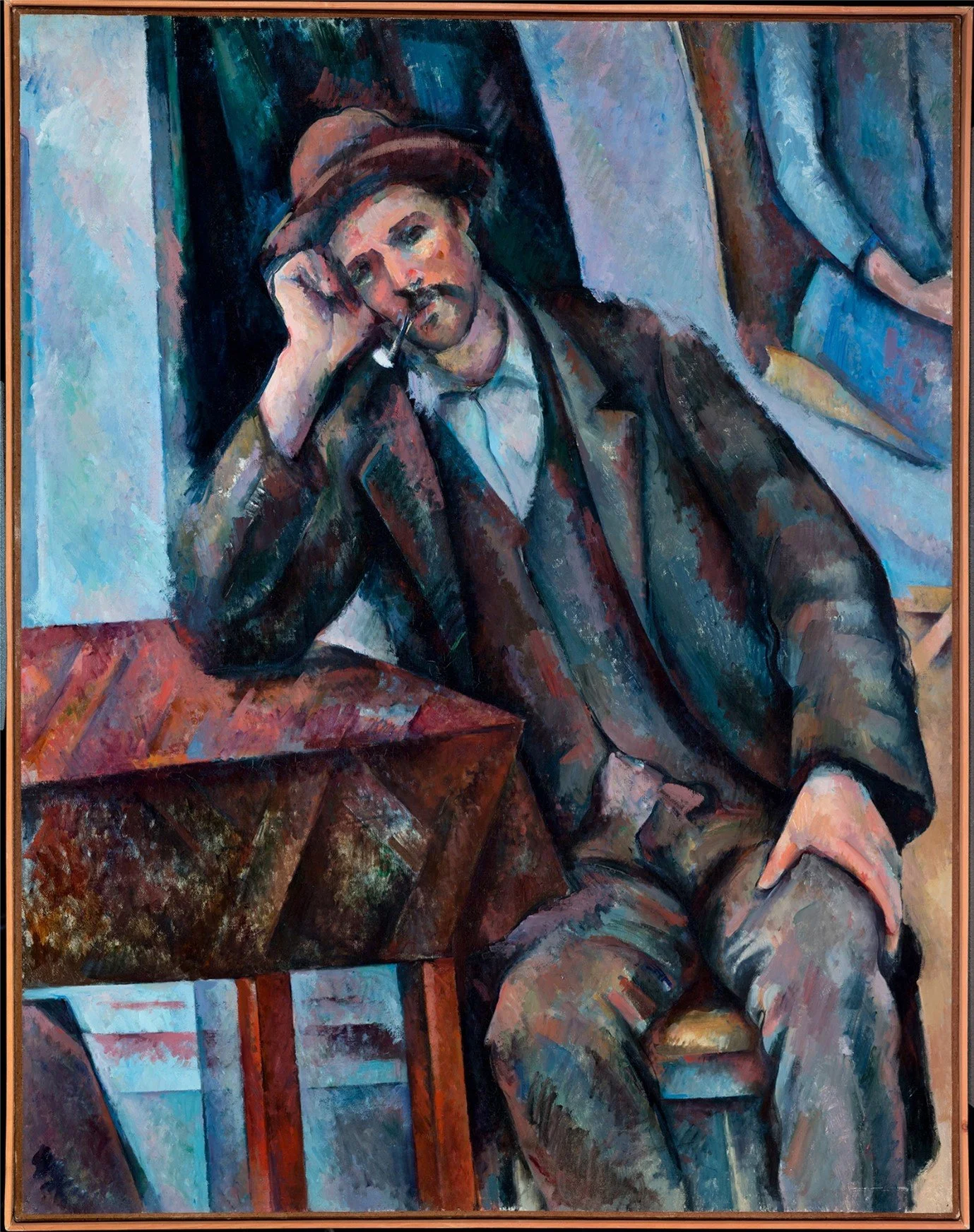

Cezanne lived at the time when the Extractive Industrial Revolution began seriously to burn the earth’s resources like never before. This was the era we mark as ‘zero’ to count the rise in global temperature.

We’re now well above 1⁰ degree higher than that era, and are very likely to reach 1.5⁰ degrees in the next decade or so. If we do nothing now, the speed of the warming will increase.

At 2.5⁰ degrees of warming, the increase will be nigh on irreversible.

It is the gradation of tones of the blue hue that elaborates the richness and diversity of different values.

The richness and diversity of different values allows us to behold the blue vase floating in the graciousness of spaciousness.

The modulation of the different values locates the blue vase within its dynamic environment.

It is the sensitive integration of deep and positive Value-systems that will co-create a space for the richness and diversity of different values.

Our future lies in the elaboration and refining of the richness and diversity of different values that will fulfil and fill full the gracious spaciousness necessary for a new era to thrive.

The modulations of different Values hold the potential for the rewilding of earth’s biodiverse environment.

It is the high-keyed hues and the chromatic intensity that exhales luminosity in refined harmony.

It is the vertical framing within framing that invites us to be still.

It is the horizontal diagonals that rock us back and forth into dynamic depth.

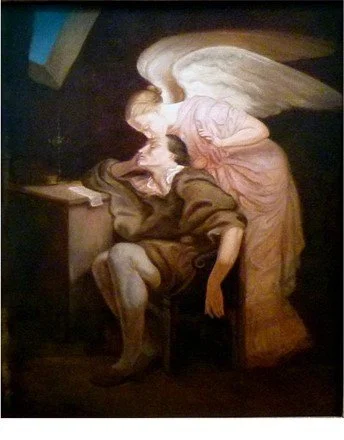

It is within the light of refined harmonies that spiritual activism will thrive.

It is within the vertical framing of connections with all beings below and above that our stillness will be receptive.

It is within the horizontal framing of our agency that we will hold our intention for goodness.

It is the shadow under the biscuit plate, connecting with the apple, that anchors the blue vase and pushes it towards us as a cool invitation to connect with us.

It is the shadows between the tall bottle of rum, the biscuit plate and the squat bottle of perfume that locate the depth of the table plane.

It is the two adjacent pieces of fruit that are sufficient but not complete: they are in the process of becoming.

It is in our shadows that there is an invitation to connect with our deepest selves.

It is in our shadows that we can locate the depth of our potential.

It is through our shadows that we will be able to become more fully human.

It is the expansive lyrical movement of the bouquet, with its shapeless spots, of red, green, white and blue, that reaches out to the limits of the frame within a frame.

It is the perpendicular scaffolding of the whole frame that maintains the presence of the blue vase.

It is the presence of the blue vase in its simplicity and complexity that speaks to us of reverence.