1839

Paul Cezanne born 19th Jan

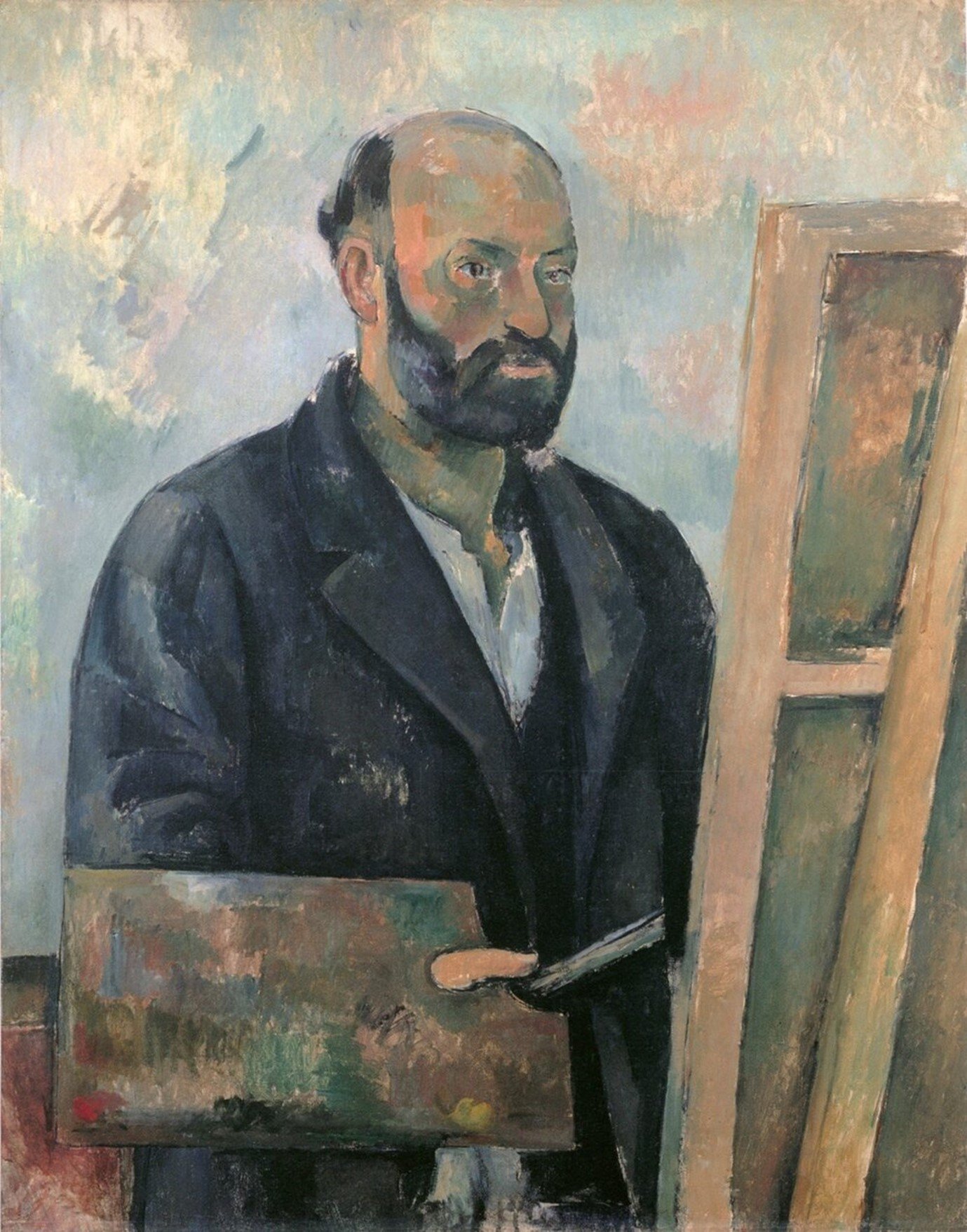

1887

Self Portrait with palette FWN 499 92cm x 73 Zurich

There was always a deep deep tension, if not a paradox, within the very heart of Cezanne’s strivings to express himself before a motif with oil-paint on canvass. It morphed through-out his life: sometimes enraging; ofttimes retreating; between times, lost and found; in good times enthralling in human company; in bad times drained by inhuman criticism; in younger times overzealous of the protection of personal space; in elder times soothed by the tender touch of pain-relieving massage; in end-of-life times yearning to be forever one with brush and mountain. I’m not simply referring to the “randomness of the tumbling flow of a life’s unfolding, gorgeous” as that often is; and, in my opinion, not expressed more beautifully than in Alex Danchev’s ‘Cezanne, A Life’.

No, I’m referring to our understanding of ‘the self’; it is here – how we understand the human self – that the paradox presents itself most acutely. For Cezanne, and we ourselves, live in the flow of the self-same narrative; a narrative of the self that was gathering pace throughout Cezanne’s lifetime. We sit within the same trajectory of the paradox as Cezanne. It is the paradox of the atomized self.

“I paint as I see, Monsieur!” Cezanne fumed to a critic. “The others see, but do not dare to paint as they see. I dare.” It was to be a key facet of the modern age, co-created by Cezanne - of Modernism – that the individual would assume a prominence far beyond that of traditional times: that someone who didn’t have any claim to status, or power, or wealth should take unto themself the right to express themselves as they saw fit: this enraged the traditional art-going public. Not simply because the works themselves were deemed not to have any depth or substance, being by their artist’s own admission, mere ‘impressions’, fleeting whims of passing associations; but that this new generation of artists seemed to care little for the foundations upon which rested the old ways.

But by 1894, the old ways, the ‘Old Regime’, was gone; and a new one was growing in its place: modernism.

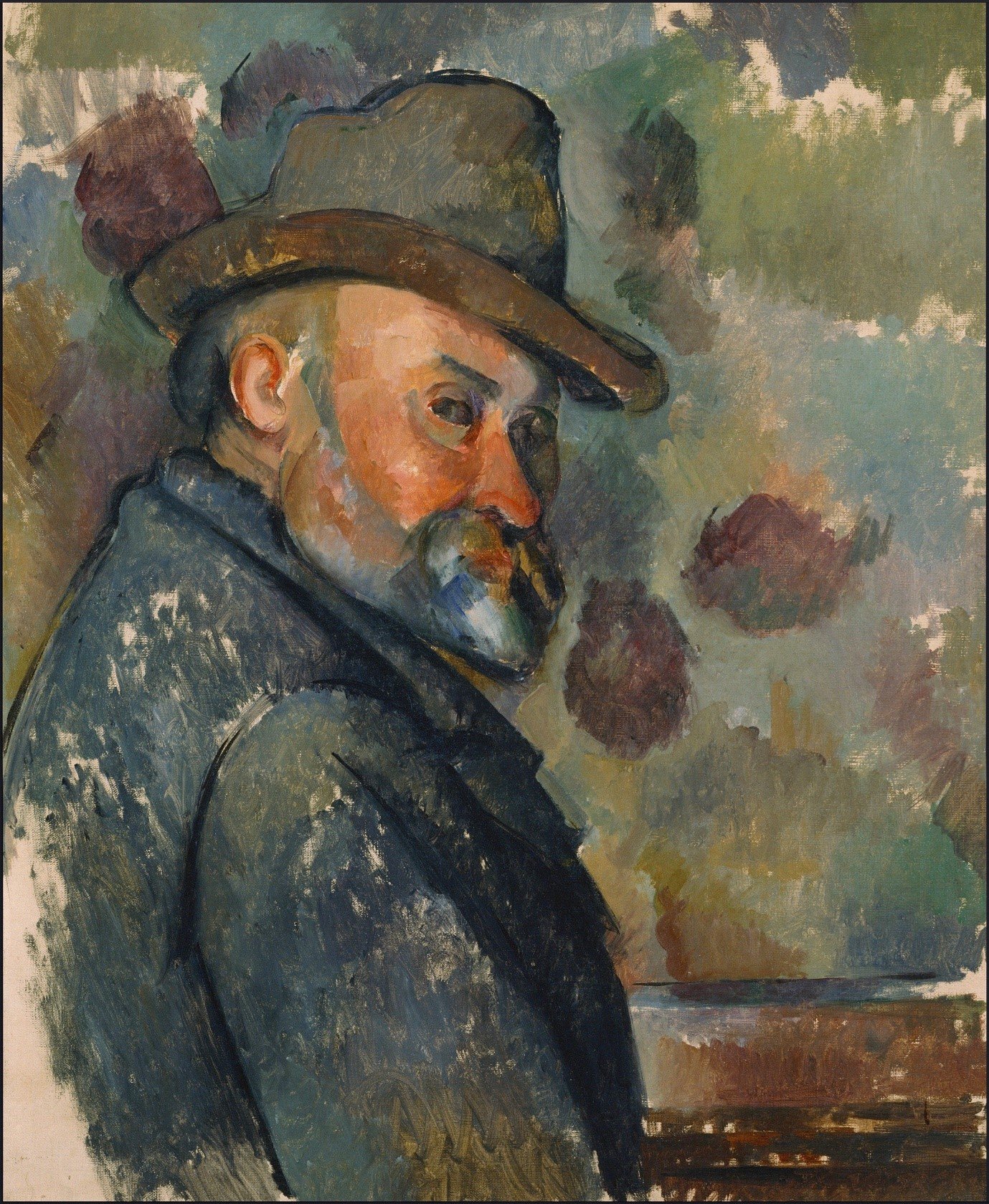

1894

Self portrait in a floppy hat FWN 511 60cm x 49 Artizon, Tokyo

“The most striking fact of the day was the misery of the industrial proletariat. Despite the growth of the economy, or perhaps in part because of it, and because as well of the vast rural exodus owing to both population growth and increasing agricultural productivity, workers crowded into urban slums. The working day was long, and the wages were very low. A new urban misery emerged, more visible, more shocking, and in some respects even more extreme than the rural misery of the Old Regime.

“From the first to the sixth decade of the Nineteenth century, workers’ wages stagnated at very low levels (in France and England), while economic growth accelerated. From 1880 to 1914, the so-called ‘Belle Epoque’, what we see is a stabilization of inequality at an extremely high level.

What was the good of industrial development, of all the technological innovations, toil, population movements - of modernism itself - if the condition of the people was just as miserable as before?”

1895

Self Portrait FWN 517 55cm x 46 Qatar

“In a way, we are in the same position at the beginning of the Twenty-first Century as our forebears were in the early Nineteen Century: we are witnessing such impressive changes in economies around the world, but inequality at an extremely high level is stabilizing”.

1900

Self Portrait of the artist in a beret FWN 529 63.3cm x 58.8 Boston, USA

1906

Paul Cezanne 22nd Oct RIP

2024 19th January 2024

“We live in a culture that prizes the atomized self, inappropriately foisting medicine onto individuals when disease and discomfort are the multi-causal snares of systems of oppression within which we are stuck like flies in a spider’s web. We think we must heal individually and succeed individually. We are taught, also, that we feel and sense individually, keyed only to direct contact with our skin-delineated corporality. This preoccupation with personal health and personal responsibility for health as primary, has led to the detriment of understanding that the health of one person is intimately tied to and representative of a whole population. Illness, trauma, and pain do not belong to an individual; they are a web that includes the individual self”.

Illness, trauma, and pain do not belong to an individual; they are a web that includes all our selves.

We see the same stabilization of inequality at an extremely high level.

We sit within the same paradox.

We can strive, together, to move through the paradox.

It is the work of a lifetime and beyond!

With thanks to the writers, in quotation marks, Roger Magraw, Sophie Strand, Mary Oliver, Thomas Piketty, Alex Danchev, and of course, the Integral Dynamics of Ken Wilber.