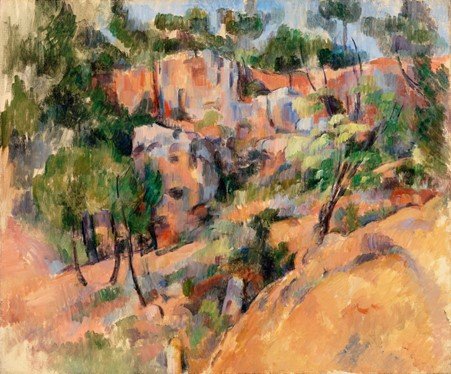

Bibemus FWN 305 46.3cm x 55cm 1894/5 Barnes Foundation

This mini-series of four posts focuses on three paintings by Cezanne, all with the same motif – Bibemus Quarry – and all painted in a two-year period 1895-7, in Cezanne’s ‘mature phase’, when he was just a few years shy of 60. For me, it is clear that these paintings represent Cezanne’s understanding of his own development; he now sees clearly the stages of his own growth, and expresses that development in the mode of communication in which he is most proficient – oil paint on canvass. The beauty of growth is that it is the expression of your deepest yearnings; the truth of growth is that it requires dissonance, pain and resolve; but the goodness of growth is that it lifts you beyond yourself to wider horizons. I hope you enjoy this mini-series.

Sometimes it can take a lot to leave a group. You maybe expect to be treated the same as usual, but you’re not; there’s a distance, an invisible border, a forcefield. Leaving the tribe, forsaking the common purpose, is the worst sin of all!

In 1873, the Impressionist Group was so strong that they formed themselves into the ‘Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes-Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs, etc’. They were ‘anonymous’ because it was still illegal for people to band together. The abuse aimed at Cezanne from the general public and critics alike so depressed Cezanne that he didn’t send any paintings for the 1876 Impressionist Exhibition. It would be Monet who persuaded Cezanne to exhibit again; and he does so with gusto! But by 1879, Cezanne has realised he must leave the group, and happily, this time, not because he was hurt by artistic criticism, though he still received more than his fair share; but for reasons much more difficult for the group to understand.

This is the first of three paintings of Bibemus Quarry that I will present as a series, all three painted within a two-year period, late in Cezanne’s development, 1895 – 97. There were many such quarries between Aix-en-Provence and Montagne Sainte Victoire, worked decades ago, even centuries, in a sporadic fashion, and then left and forgotten. For a few years, Cezanne became fascinated by this particular one, and he was able to rent a stone cabin nearby to rest and keep all his stuff in.

Back in the 1870’s, Impressionist paintings were criticized for three reasons: firstly, they were common and vulgar! The Impressionists painted ordinary life and ordinary people, nature, streets and cities; there were no noble and awesome scenes, no majestic kingdoms, nor rural peasants happy with their lot. Their paintings were verging on the revolutionary!

Secondly, their paintings were painted outdoors, in the full glare of the sun. The paintings assaulted the senses of the exhibition-going public! Many swooned and fainted, so bold and glaring was the use of vibrant colours. They seemed to have no respect for the well-established traditional techniques of classical painting: depth and shadow were represented by different bright colours, not darker fading. Their paintings were almost childlike!

Thirdly, the paintings were unfinished and crude: you could see the brushstrokes of the paint quite clearly; the paint was even pronounced and seemingly haphazard, rather than hidden and polished! It was rough and uncivilized! Objects were not clearly delineated and tended to merge into each other creating a fuzziness that undermined the intellectual and normative aesthetic of art itself: which, the critics maintained, should be to reinforce the moral certitude and noble standing of civilization.

Classical art was a product of the context within which it developed. The most important object of the painting was the one most visible, with all else fading away in a supportive role; mere acolytes for the enhancement of the main motif (usually involving a man). It was hierarchical, in its subject matter, its construction and its presentation.

The influence of the old ways had faded; and the Impressionist group of the 1870’s had expressed in art what it felt like to be modern! In place of hierarchy, and in the spirit of this new democratic era, through the use of vibrant colour, they sought to celebrate the radiance emanating from each object on the canvass. They sought to invert hierarchy by presenting the beauty of ordinary things; and presented objects in the distance with emphasis relating to their impact not their position in depth – the last shall be first, and the first shall be last! That was the Impressionist purpose: to create an art for the modern era, liberated and adventurous, vibrant and radiant, emotive and engaging. Liberty, equality and fraternity expressed through the application of paint on canvass.

But Cezanne is not painting this painting as part of the Impressionist movement: that was twenty years ago! He’s painting this painting in 1895, not 1875! What I think he is doing is trying to capture the essence of the movement, so that, as he moves beyond it, he can include it as part of his development.

There’s a joyfulness about Impressionist landscape painting; as if they say - “hey, we’re just going to paint the stuff of ordinary life, because that’s where beauty lies. And we’re going to paint it in a way that offers an invitation for you to feel the rich atmosphere that we paint. We’re not interested in the precise detail of the motif; we’re not interested in attaining such a polished finish that you can’t see the paint. We want to be raw, honest and simple, rich and vibrant, joyful and inclusive.” Their higher purpose was in remembering that beauty is the beholding of the graciousness of ordinary life; how freeing that sensation was, encapsulated in paint on canvass, panoramas of our earth in sunshine and breeze.

Here is Cezanne, twenty years after the Impressionists made their mark in history, celebrating the essence of their achievement.

This is how we did it!