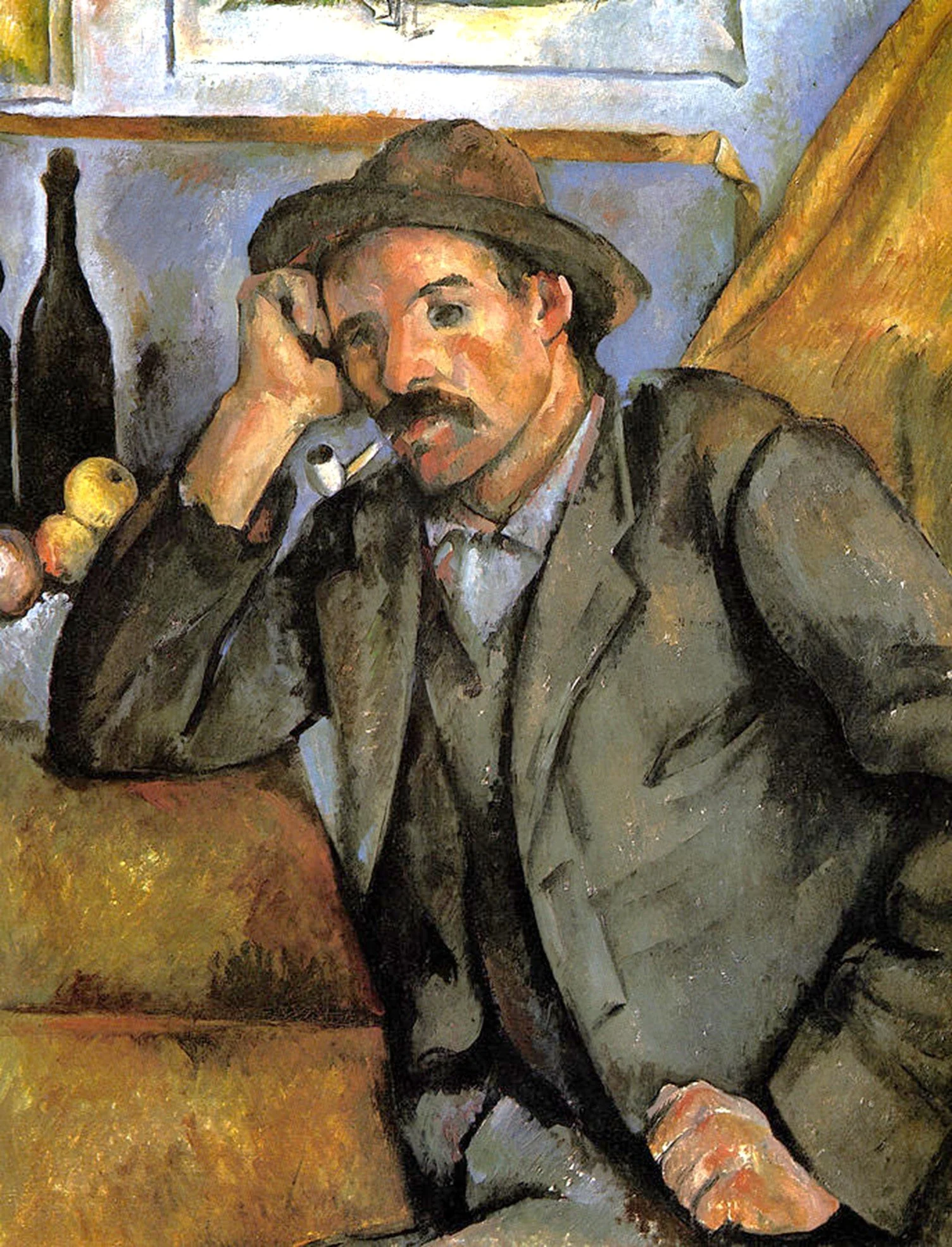

The smoker leaning on his elbow FWN 505 1891 92 cm x 73 Kunsthalle Mannheim

This is Paulin Paulet. It’s a solid representation of the guy, as he looks us straight in the eye, without deference or favour, without excesses but with sufficiency, without joy but with intention, without motion but prepared: earthy and weathered, strong and undramatic, plain and unromantic, determined and unsentimental. He wears his well-worn working shirt, waistcoat and jacket as he takes a rest, next to the woodburning stove, leaning on the table covered with a tablecloth relaxing with his favourite clay pipe. He's a farmworker having a rest at home in the promising new republic that is the Modern France of 1891.

Historians of the 1970’s would interpret the period during which Cezanne painted a set of three portraits, which we call ‘The Smoker’, as the era when “peasants became Frenchmen” (Eugen Weber 1976). I’m reminded of the occasion in a fashionable café in Montmartre when Cezanne, dressed in traditional earthy clothes, and speaking in a rough Provençal accent, refused to shake people’s hands because ‘he hadn’t washed for a week’! Weber’s analysis adds more poignancy to the story: Weber claimed, justifiably it seems, that at the beginning of the 1800’s, most people-who-lived-in-France communicated in their local dialect, not in (Parisian) French. Though French had been the official language for many generations, only half of the population spoke or understood standard French; the southern half of the country continued to speak Occitan languages (such as Provençal), and other inhabitants spoke Breton, Catalan, Basque, Dutch (West Flemish), and Franco-Provençal. In the north of France, regional dialects of the various so called ‘langues d'oïl’ continued to be spoken in rural communities.

Various things contributed to encourage a changing dynamic: the decline of rural society and corresponding growth in urbanization, national military service, and changes in social patterns – from shopping and entertainment, to working and the production of affordable bicycles, ‘universal’ suffrage (men not women!) and changing employment patterns (the growth of schooling, education and civil service). At the start of the century, the leaders of the French Revolution had established a National Property Register, and gradually the French State assumed the responsibility for recording and protecting property rights, supplanting the power of nobles and church. This marks the birth of the modern state, where the sacralization of wealth was the price paid by the working poor for gaining voting rights. The process is symbolically baptized by the adoption in 1891 of Unified Time through-out the whole of France - made necessary to produce accurate timetables for the expanding railway network. The centralized State had arrived, directly and quickly connected to all the ‘Departments’ of France.

Weber maintains that it was a period in which the peasants were ‘modernized’: recognizing themselves as ‘French’ (rather than ‘Provenćal’, or whatever), and politicized (able to vote). I suspect Cezanne, whether he considered himself Provençal Occitan or French, he certainly did not consider himself French Parisian! It was Paris he had wanted to conquer, albeit with an apple!

The year of 1891 was a strange year for Cezanne. He was back in Provence: very happy doing his own thing. The Impressionist movement had come and gone; and all kinds of ‘movements’ had replaced it – post-impressionism, neo-impressionism, symbolism – with lots of different artists with unique ‘temperaments’. Famous names we all know – Seurat, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and more…It didn’t bother Cezanne much these days; he was focused on his own work. He no longer sort recognition, nor did he need it now – financially nor spiritually! The days of wheeling paintings in a wheelbarrow for acceptance at the annual Academy de Beaux Arts were long gone; as also were attempts at displaying his paintings at exhibitions. He was no longer interested in reaching out to the art-world; he was no longer trying to change the world! But now, all of a sudden, the art-world were interested in reaching out to him!

Paul Alexis published his book, a fictional novel with a cast of three: the leading light of the previous generation of artists, the artist Manet; the jazz musician, who played his music by colouring the notes of the piano, Cabaner; and a character called ‘Poldex’ aka Paul d’Aix (Cezanne). The artist Signac was writing about four canvasses that Cezanne gave to Alexis. The political writer Felix Feneon claimed the ‘Cezanne tradition’ was being ‘diligently cultivated’ by the abstract artist Seruzier, the Danish Modernist artist Willumsen, the post-Impressionist painter and writer Emile Bernard, the post-Impressionist artist (friend of Gauguin) Schuffenecker, the artist Charles Laval, Henri-Gabriel Ibels, Charles Filliger, and Maurice Denis and others. The novelist and art-critic Huysmans re-published an article he had written ‘Paul Cezanne’; and Emile Bernard published his article of the same title, in the series ‘Men of Today’. This last publication also featured a drawing of Cezanne by Pissarro on its cover.

This was the context within which Cezanne was painting the three paintings of our Paulin Paulet, ‘The Smoker’. While France, or rather the modern French State, was growing in power and prestige in a period of peace and expansion (aka colonialism!) and all the art-world, or rather the Parisian modern art scene, was focused on ‘the Cezanne tradition’, Cezanne himself was more interested in the latest volume of ‘The Origins of Contemporary France’ by Hippolyte Taine published in 1891, entitled: ‘Modern France’. Here, Cezanne read: “Indeed, the Old Regime and the Revolution are, from now on, complete wholes, completed and closed periods; we have seen the end of it, and it helps us to understand the course.” wrote Taine in the intro. People-who-lived-in-France had become French, and were well aware that France and its people were undergoing a major transition in its history; as we undergo a transition today, but an even more critical one. And like Taine, and Cezanne, we also try to ‘understand its course’.

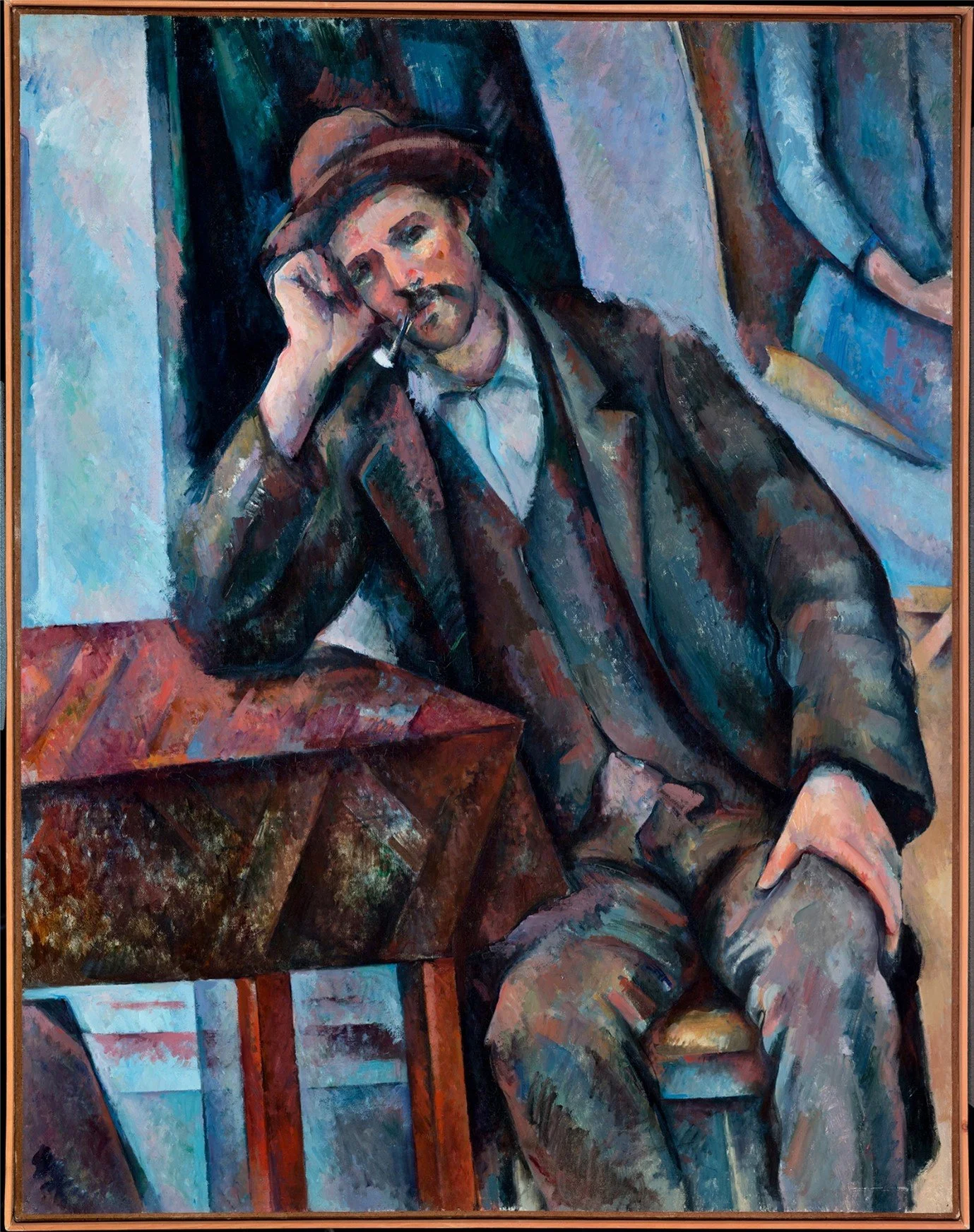

Cezanne’s response to the ‘course of history’ was to paint three portraits of a guy smoking a pipe. In this second painting, gone is the traditional genre painting of the rural peasant: Paulin Paulet is now in the midst of Cezanne’s studio, with a few of Cezanne’s paintings as the backdrop.

The smoker leaning on his elbow FWN 506 1891 91 cm x 72 Hermitage

The artist’s studio now becomes the milieu, within which Cezanne places Paulin. Here, we’re not any longer sure what is meant to be ‘real’: the fruit and bottle appear at first glance to be on the table behind Paulin’s leaning elbow, but on closer inspection we see that they are part of a still-life canvass; the thick brown line above them is the edge of that still-life canvass! Here, we have the same guy, in the same clothes, in the same pose, but now painted with as much blue as brown, fuller warmer colours, and paintings within a painting. This painting is not simply the depiction of a rural worker, nor is it simply a painting of an acquaintance of Cezanne. It is Cezanne’s response to understanding the course of Modern France.

In his analysis of ‘Modern France’, Taine introduces a key analytical concept that he calls ‘milieu’, and that we might recognize as ‘context’; Taine wishes to contextualize his analysis within the socio-political framework that has developed in France – most notably, the emergence of the ‘State’, which has supplanted the power of the Nobles and Bishops. Cezanne was fascinated by Taine’s analysis, which he read while painting the three ‘smoker’ paintings. Zola’s analysis of France’s ‘modernity’, lays stress on the importance of the temperaments of the individuals involved; and this was how Cezanne had understood the ‘course of history’ up until now. Cezanne was fascinated by the idea that milieu or context could play an equally important role in the course of history. Within a couple of generations, these two different analytical approaches, Zola’s imaginative individual and Taine’s milieu, would have developed into different philosophical outlooks: existentialism and system’s analysis.

The Smoker FWN 507 1891 91 cm x 72 Pushkin

In this last of the three Smoker paintings, the brown of the earth has nearly all disappeared, and with it, any connotation of the farmworker. The clenched fist is replaced by an open hand with slender fingers. And most strikingly, gone is the use of conventional perspective. This space, this milieu, is rather disorienting, in which the depth and structure of the space are difficult to comprehend. The certitudes and structures provided by the traditions of the past are gone; but the worker remains, in a very different milieu.

What are we to make of the three smoker paintings? I think they are the beginning of an unfolding narrative of Cezanne’s mature and final phase of development, within the context of a Modern France. What was Cezanne hoping to accomplish? A couple of years earlier Cezanne had written in a letter: “I have resolved to work in silence, until the day when I feel capable of defending theoretically the results of my endeavours”. I think at this point in 1891, Cezanne did not know what he was doing: he just knew he had to do it; but now, more than ever, he was centered enough to trust the dynamic energy of his creative spirit, trying to be in harmony with the course of history.

There is also a sense in which he did not know what he was doing because it did not yet exist: he was painting for an era, a milieu, that had not yet happened. The Nigerian poet and novelist, Ben Okri, expresses this same dynamic energy in an article he wrote in 2021:

So a new existentialism is called for.

Not the existentialism of Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre, negative and stoical in spirit,

but a brave and visionary existentialism,

where, as artists, we dedicate our lives to nothing short of re-dreaming society.

We have to be strong dreamers.

We have to ask unthinkable questions.

We have to go right to the roots of what makes us such a devouring species,

overly competitive, conquest-driven, hierarchical.

Ben Okri

Post script. In case you wonder why Cezanne includes a portrait of his partner, Hortense, in this last version of ‘The smoker’ (top right, in blue dress): here’s my explanation: In February 1891 Cezanne’s school friend, Paul Alexis was down in Aix, and visited Cezanne to see how his friend was doing, and, probably more to the point, so that he could report back to Zola in Paris. Cezanne gave Alexis the first portrait of Paulin, and duly signed it, along with three other landscapes and still-lifes. Shortly after, another mutual friend visited Cezanne and reported to Zola how he also found Cezanne. Both letters to Zola portray Cezanne as being embroiled with his wife Hortense over money matters. The letters read rather like schoolboy banter: naming Hortense as ‘The Dumpling’ and the son, young Paul as ‘The brat’. The inner circle of Cezanne’s school friends, Zola, Alexis, Numa Coste had all given up on Cezanne – Coste writes to Zola: “one of the most moving things is to see the good chap (Cezanne) preserve the innocence of youth, forget the disappointments of the struggle and, resigned to suffering, throw himself into the pursuit of a work which he can’t deliver” (my underlining). Cezanne knew what they were up to, and what was their assessment of his work. And so, in the last portrait of Paulin, painted after Alexis had gone back to Paris, he includes one of his portraits of Hortense as the context of the painting – top right (Portrait of Madame Cezanne, 1886) - to make a point!