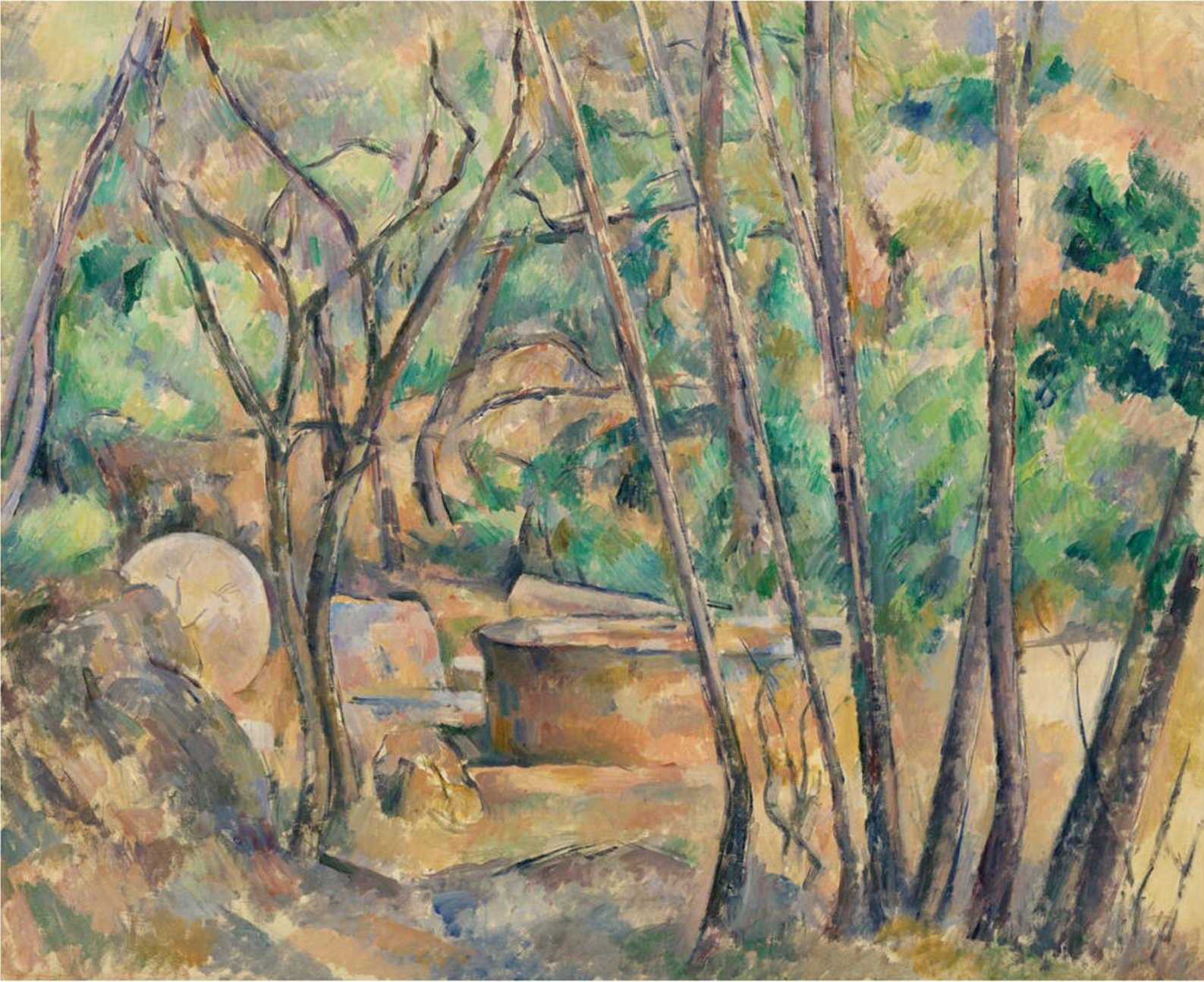

Millstone and Cistern in the undergrowth FWN 292 1892-4 65.1 cm x 81 Barnes, Philadelphia

How magical to discover a secret place where our ancestors lived and worked, allowing us to wonder at the ingenuity of their craft: beholding how they integrated their survival with their environment in the circle of life; feeling the pull, the fanning, towards the light of a more complex existence; acknowledging the harmony of what is far away and what is near, in the exquisite tapestry of complementary hues.

Far from instilling terror, as Cezanne’s paintings did in his day, this painting delights!

This is the way that our ancestors had lived for many thousands of years: gathered around water and grain, millstone and well. Here in Provence, millstones were wrought from a rock called Pierre Meuliere, and were water-driven till the 1880’s. Within Cezanne’s depiction of this pre-industrial age, we feel no urge to return, no nostalgia; but rather, we do feel a certain connection and a certain curiosity.

“Grinding wheat is an art. One might think that extraction of flour consists simply of mashing cereals between two stones. It is in fact an activity that requires a great deal of ability on the part of the miller. The millstones must spin at a specific speed and they must maintain a specific distance of separation. They also require a regular dressing with a hammer to maintain their abrasiveness. Above all, not just any type of stone can be used. A stone that is too soft and supple will only tear the wheat to shreds and not extract the bran. On the other hand, a stone that is too hard turns the flour into a fine dust that is difficult to bake and contains oil that prevents its conservation.” La pierre à pain

Cezanne displays the scientific artistry of our ancestors, set out centrally for us to acknowledge and admire: the circle of the millstone, the rhomboid of the supporting stone, the ellipse of the well, and the triangle of the stone leaning on the well. These were their tools, abrasively fine-tuned and geometrically accurate – fit for purpose. This is the way humans had adapted their environment to enhance their existence – stone carved, water channeled, grain harvested, sun drenched within the circle of life. Their greater purpose, the great work of their era, was to teach us about the importance of belonging, as they gather around water and grain. We are the humans that owe our existence to these ancestors, to the harmony they created, and the treasure of belonging.

And this is the harmony within which Cezanne applies earth oxides and pigments onto canvass. The artistic compendiums and works gathered in the museums of Cezanne’s day are the cultural products of our ancestors’ ways. Cezanne has learned to understand them not as a prison but a liberation; something to include, but go beyond. Within the flow of this harmony, Cezanne transcends traditional artistic techniques. If we compare the photo below with Cezanne’s painting, we see how Cezanne has reversed the traditional technique for the expression of perspective: he makes the foreground smaller, and the background larger.

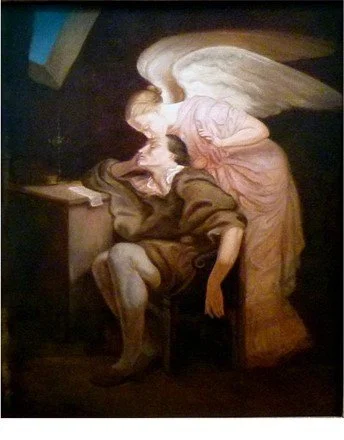

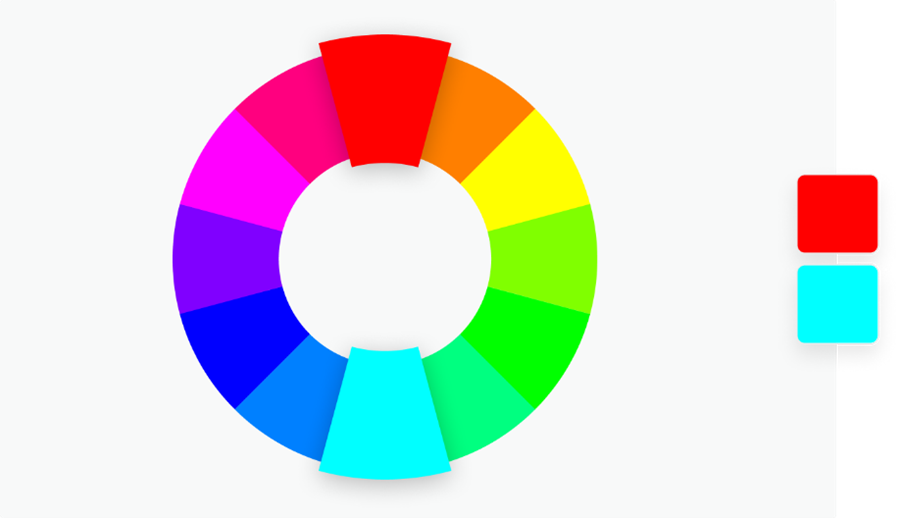

The same is true of Cezanne’s use of colour: he does not abide by the traditional method of fading a hue to signify depth – the traditional effect of modelling light by the gradation of colours, chiaroscuro, developed by the Renaissance Masters. This is how he was taught to paint at art-school: the inheritance from a by-gone age. Below is the original of Felix Nicholas Frillie’s Kiss of the Muse in traditional artistic style and below that, Cezanne’s copy from 1860. At this time, Cezanne, aged 21, was copying the lesser well-known Masters, in the museum in Aix. He was studying law under orders from his father, but being taught to paint by Monsieur Gibert in the Ecole Gratuite de Dessin. Cezanne had won second prize for a portrait he painted the year before, but for some reason, Monsieur Gibert advised Cezanne’s father not to allow him to go to Paris. Zola was already in Paris and eager to “establish an artistic society to form a powerful union for the future, to provide mutual support, whatever positions might await us”. As we can see, Cezanne was already accomplished in traditional artistic methods.

Felix Nicholas Frillie Kiss of the Muse 1857

Cezanne’s Kiss of the Muse, d’apres Frillie FWN 572 1860 Museum Granet, Aix-en-Provence

It is one thing to acknowledge and include the heritage of a past era, but yet another to develop the creativity needed for the emergent future. It is this task that Cezanne sets about achieving in his mature phase. It is his belief in the value of this task that motivates Cezanne. It is one of the reasons why so much of his work seems unfinished. In the attunement of his sensations to the emergent spirit of the next era of human development lies the creativity of transcendence.

The central aspect of this creativity lies in Cezanne’s construction of a painting by means of brush strokes of different hues; and to this effect, Cezanne finds himself discovering different techniques that enable the realization of a painting. I’ll briefly mention a few: colour complimentaries; the use of tension; movement within the frame. Such techniques enable Cezanne to hold in harmony together, the parts and the whole of the painting: as he often said: “progressing all the parts all at once”.

Cezanne has developed a wonderful intuition for combining different coloured brushstrokes together in harmony. This intuition was confirmed when, in 1854, a chemist working in a weaving factory, sought to find an answer for his weavers who complained that when they put complementary coloured weave next to each other in the tapestry, the colours became extra bright; and, more annoyingly, when they put juxtaposed weave together, the colours seem to modify the hue. So it was that Chevreul eventually published his book: The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colours; and so was born “The Law of simultaneous contrast”.

Cezanne uses two pairs of complementary colours, grey-blue and orange, and reds and greens, working together in the exquisite tapestry of the foliage in the background. He places them not too close, but just close enough to heighten their brilliance. This has the effect of giving equal emphasis to each and every part (expressed as a hue) of the motif.

As we have mentioned, Cezanne reduces the size of the trees in the foreground, but this is not simply just to reverse traditional perspective, but also to create a controlled tension between the trees themselves. Cezanne makes all the trees virtually the same thickness through-out, but it is the spacing of the tree trunks and the treetops that creates the movement: like a fan, opening out towards the light source, which is to the right – at the verdant foliage of the leaning tree. This has the effect of suggesting a secret place – behind the fan of trees.

In the photo, there is a path leading towards the centre-right of the motif; Cezanne removes this path and replaces it with a frontal plane of bluish-grey, which cuts off the bottom-left hand corner of the painting. This encourages our eyes in a movement around from the bottom left corner, up the bluish-grey, in between the parallel trees and their gentle arch towards the centre, around the top of the foliage, and back down behind the fan of trees to the right. This brings what is far away and what is near together as parts of the whole.

To sum up: it is in replacing traditional painting techniques and using pure colour to construct form, that Cezanne can give equal emphasis to each and every part of the painting; the trick is to do this, while holding each and every part in harmony with the whole. Cezanne replaces the hierarchy of traditional painting with an active democracy of each and every part!

In his 1906 eulogy, Theodore Duret wrote of Cezanne: ‘This man whose art has seemed to resemble that of a Communard or an anarchist, whose work has instilled terror in directors of the (Ecole des) Beaux-Arts … never suspected he might be seen as an insurgent.’ Cezanne, I’m sure, did know that he painted in a new way. This new way was not simply because he followed his ‘sensations’, but also because those sensations were attuned to the spirit of the emergent future, the value-system of the next era in human development – our era.

Far from instilling terror, this painting, now, in our day, delights us!

It seems to me that some confusion lies

when we mix up ideas of occasion and causation;

at one second per second, time it flies

in a sequence, but not a consequence.

“What has been, has been; and we have had our hour:

not heaven itself upon the past has power!”

But the past does try to impose its ways:

“This is how we’ve done it from our ancestors’ days”!

If we listen to the yearning within

deep in our soul, we’ll know where to begin:

let our present be shaped by our longing

and not confined in our past’s belonging.

Mike B, with thanks to Horace