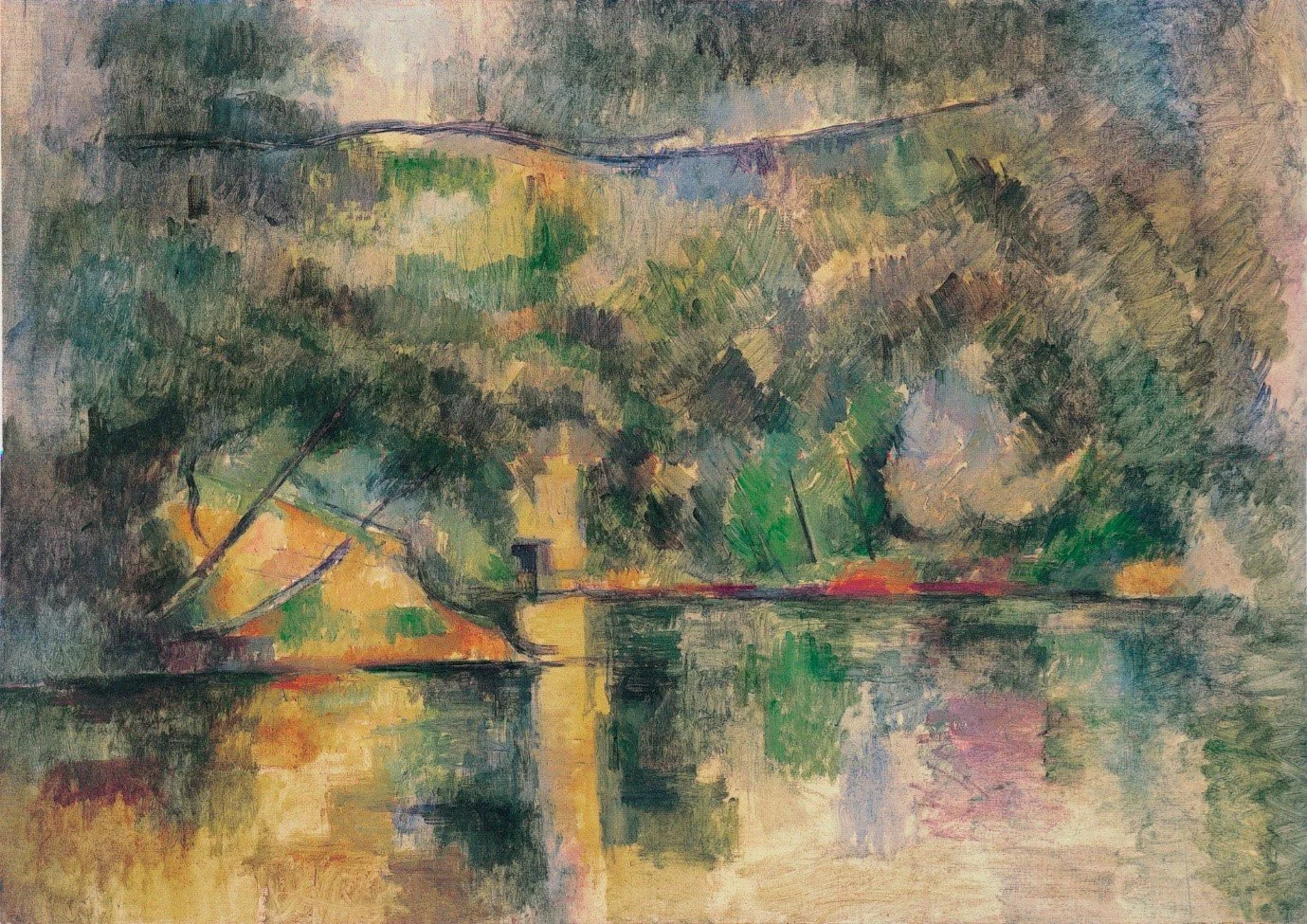

Reflections in water FWN 284 1892 – 4 65 cm x 92 Ehime, Japan

This series of blogs concentrates on Cezanne’s ‘mature phase’: the phase is a wonderful paradox of an intensity of focus and freedom of expression, of self-confidence and of self-yeasting, of mountain and quarry, of panorama and undergrowth, of huddled card-players and expansive bathers, of kitchen tables of fruit and bedroom tables of skulls, of watercolour and oil. At the deepest level of evolutionary consciousness, it is both re-wilding and emergent creativity.

“Right now, a moment of time is passing.

We must become that moment”

Cezanne

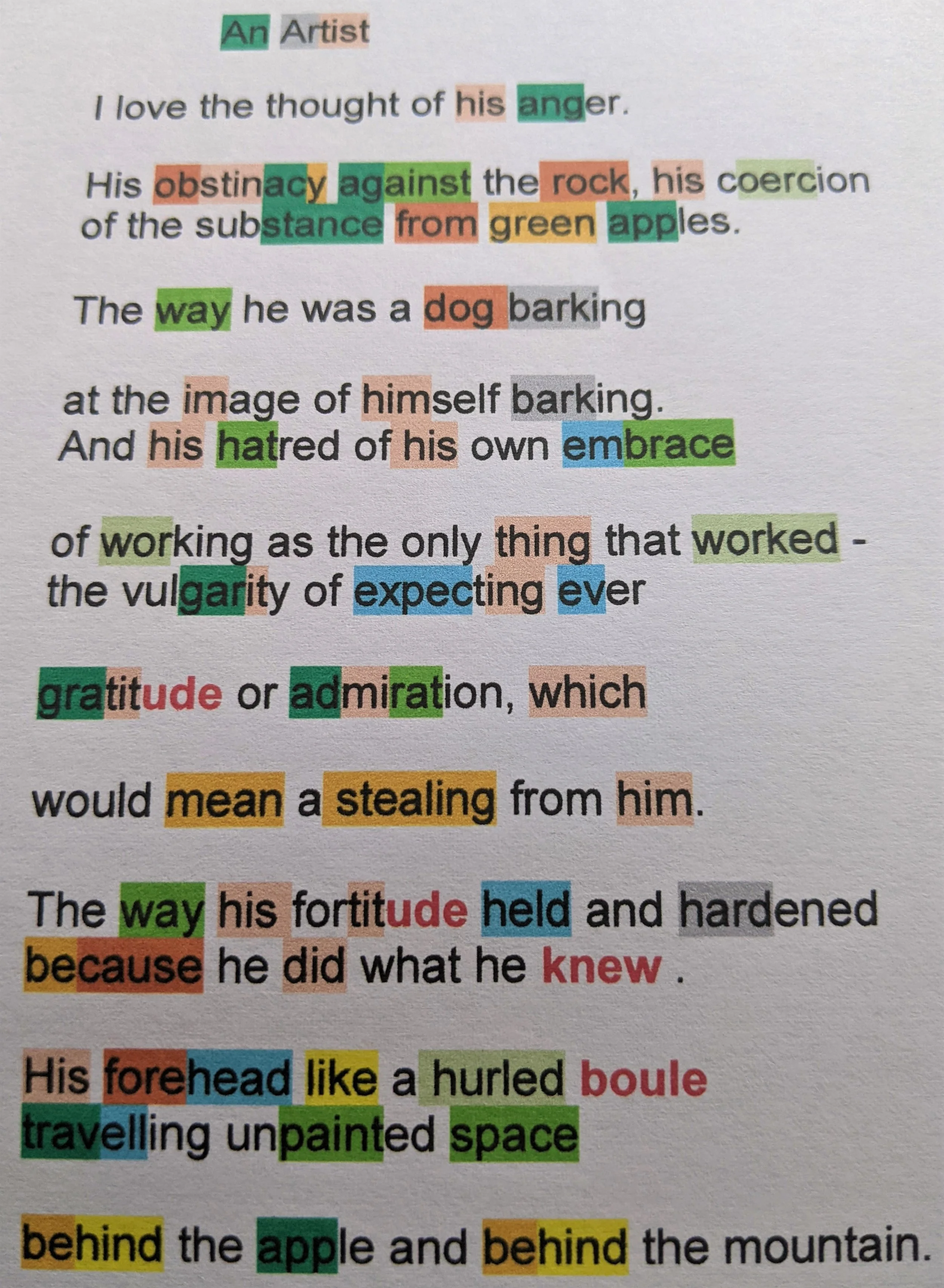

Seamus Heaney: An Artist

Exactly when his mature phase began is a matter of debate, but one thing is for sure: that there was a noticeable change, a turning, in Cezanne’s artistic expression around this time, and that this phase saw a blossoming of Cezanne’s oeuvre. This ‘turning’ has been described by various critics in different ways; and I will concentrate on it in this blog, as an introduction to this series.

In his book of 1927, ‘Cezanne A Study of His Development’, the great Cezanne devotee and critic, Roger Fry selects this landscape as one which expresses “the latest manner of our artist” (p.80); ‘It would appear’ Fry continues ‘that there was at the end of Cezanne’s life a recrudescence of the impetuous, romantic exuberance of his early youth. It is deeply affected and modified by the experience of the intervening years. There is nothing wanton or wilful about it, nothing of the defiant gesture of that period, but there is a new impetuosity in the rhythms, a new exaltation in the colour.’

Fry continues with a brief analysis of our painting: ‘The landscape of a pool overhung with foliage gives an idea of the disintegration of volumes…It is quite true that in nature such a scene gives an effect of a confused interweft, but in earlier days Cezanne either would not have accepted it as a motif or would have established certain definitely articulated masses. Here, the flux of small movements is continuous and unbroken. We seem almost back to the attitude of the pure Impressionists. But this is illusory, for there will be found to emerge from this a far more definite and coherent plastic (flexible) construction than theirs. It is no mere impression of a natural effect, but a re-creation which has a similar dazzling multiplicity and involution.’

Cezanne had moved up a gear; he was now in overdrive!

I would place Cezanne’s final phase of artistic development from 1888. It was in the year of 1888 that Cezanne painted the Chantilly Forest three times: the last of which marks the beginning of “the latest manner of our artist”. These three paintings mark Cezanne’s realization that he has been on a journey through stages of development; and more pertinently, that he himself can ‘manage’ this development simply, in the first instance, by acknowledging it. In that realization lies his rejuvenation and his freedom (his ‘recrudescence’, as Fry describes it).

In his poem above, Seamus Heaney describes it in the colours of Cezanne and in these words: Cezanne could now “do what he knew”. In a previous blog, I have explored the idea of ‘lines of development’ in relation to the three Chantilly paintings, and later in this series I will concentrate in particular on the spiritual line of development observable in Cezanne’s oeuvre.

For now, let me try to describe what I understand to be the basis of the ‘turning’ that Cezanne experienced in those late years of the 1880’s. Underlying Cezanne’s mature phase of painting was the implicit realization that at its deepest level, the creative spirit is emergent. Cezanne’s understanding has flipped: the creative spirit is not confined within the personal, simply existing within us, in our heads or our hearts; rather, we exist within the creative spirit. There is a profound sense in which the creative spirit is received as inspiration: that such inspiration comes from without, but connects deeply within. In the act of painting, Cezanne was indeed connecting with the creative spirit. It is in this sense that the creative spirit is ‘transpersonal’: the creative spirit is not less than the personal, but rather it includes and goes beyond that which is personal.

We will examine in later blogs more precisely what we mean, but suffice for now to say importantly what it does not mean. By this ‘creative spirit’ I do not mean to offer a name for ‘God’, or a ‘divine being’. I want to indicate that there is a ‘creativity’, a ‘creative spirit’, at work at all levels of existence – it is what I mean when I say that one of the elements we see within our universe is that of including and transcending; our universe seems to function in this way. The idea of the creative spirit indicates both that our world, which is continuously greater than the sum of the parts, is in the process of being created, and that it is thereby transpersonal.

Because the creative spirit is transpersonal, it does not belong to any one individual or being; it cannot be owned by any one individual. Individuals can connect to the creative spirit, with intention, practice and self-criticism. When we participate in creative activity, we feel it in the deepest whole of our being. This is what I mean when I use the word ‘spiritual’, and through-out this series of blogs I will examine Cezanne’s spiritual line of development in greater detail, and I hope, in greater clarity.

It is this stage of spiritual development that the thirteen century Persian poet Rumi describes thus:

I have lived on the lip of insanity,

wanting to know reasons,

knocking on a door.

It opens.

I’ve been knocking from the inside!

Rumi