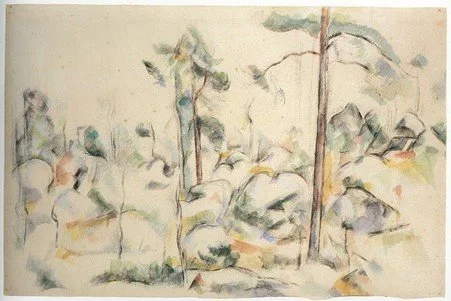

Mount Sainte Victoire viewed from Gardanne FWN 297 1892-95 73 cm x 92 Yokohama

Cezanne was so happy to be back: it was here he had fled, some five years ago, with Hortense and young Paul, from his blood relatives, and from life, into the little village of Gardanne. It was here where he had come to terms with the mental strain of life as an artist, one who was trying so hard to find his own path, and not be knocked this way or that: he thought he could withstand the criticism of the general public, and the art critics of the day, but it was the criticism of his closest friend, Zola, that had been the last straw. It wasn’t so much a criticism of Cezanne’s work either; even worse, it was, rather, the end of an intentional relationship. They had vowed to change the world, together; and that was now gone. Zola had lost faith in him. That sadness would remain deep in his soul. It was here, in Gardanne, that Cezanne had managed to reconcile himself to that deep sadness, and so escape that depth of depression when you, and all around you, seem to swirl into a downward spiral of emptiness. Cezanne gave thanks that it was here that his healing happened.

In this painting across the interlocking landscape looking away from Gardanne, across to La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, Cezanne would choose the soft and warm colours of the Impressionist movement. When he painted this particular painting, the impressionist movement was twenty years ago! Memories of those days flashed through his mind – how the local people of Aix, having declared a Republic following the lead of the Communards in Paris, nominated him as Director of Arts. Who’d have thought it! But that was before the bloody and brutal re-possession of Paris by the ‘Emperor’, in league with the Prussian conquerors. Zola had stayed in Paris – reporting on the atrocities he witnessed; typical Zola! While everyone else was lying low.

And then, a couple of years after the bloodshed, amongst the ruins of Paris, Cezanne had met the peaceful anarchist Pissarro. What a transformation they had achieved, together. He had walked and talked with Pissarro around Auvers and Pontoise, and they had painted together, outdoors, in the open air, with an airy, light, warm and colourful palette. That’s how he would paint today, twenty years on. It was proof indeed that he had come to terms with the turmoil of his life thus far. He felt a certain serenity and strength.

And what’s more, this was the mood through-out the whole of France. The brief rise of nationalist patriotism of the late 1880’s – calling for France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian war to be avenged, and the return to an Imperial France – had passed. The people of France chose firmly in favour of the Republic: the Republicans were victorious in the 1893 General Elections gaining an increased majority. Provence was rediscovering its own traditions, and what it meant to be a Republic; happy to elect reformist leaders; Prime Minister Léon Gambetta was the son of a Marseille grocer, and future prime minister Georges Clemenceau was elected deputy of neighbouring Var in 1885. The paths of Cezanne and Clemenceau would soon cross, through the auspices of the person who had been the organizer of the Impressionists, Claude Monet – ‘he’s just an eye’ thought Cezanne ‘but what an eye!’.

France had finally embedded the transition instigated by the first French Revolution of nigh on 100 years ago. With hindsight, and using the resources so abundantly left by the revolutionaries (the systematic and detailed records of wealth, inheritance, tax returns and so on), we can now see that France had made a transition from a ‘ternary society’ to a ‘proprietarian’ society; from a society based on the three functional groups of clergy, nobility and the ‘third estate’ (the workers) - to a society based on the sacralization of property. The concentration of wealth in 1800 was such that the top 1 per cent owned 45% of private property of all kinds; but by 1914, the top 1 per cent owned 55% of all wealth. In Paris, that figure had reached 65% by 1914. So, not much change there for 100 years of being a Republic aiming for liberty, fraternity and equality! The change took place in the emergence of the ‘property owning middle class’. The wealth of this group of people – the 40%, between the poorest 50% and the richest 10% - would grow from just 15% in 1800 to some 40% wealth ownership, while the top 10% share would fall equivalently (back to around 55% - not falling so far as to make us commiserate for too long!). (Piketty Capital and Ideology). The poorest 50% have remained where they’ve always been: poor!

The make-up of the wealth of the rich had also changed since the first Revolution, within the lifetime of the young Republic: ‘the preponderance of stocks, bonds, bank deposits and other monetary assets over real estate reflects a profound reality: the ownership elite of the Belle Epoque (1885 – to 1914) was primarily a financial, capitalist, and industrial elite.’ (Piketty Capital and Ideology p.136) – ‘the upward trend in the concentration of wealth in France over the long nineteenth century was a phenomenon of ‘modernity’.

Indeed, this was one of the aspects that Cezanne loathed in his father: the self-righteousness of the self-made man, who had acquired his fortune financing others in hard times – the banker of Aix. They had ‘reconciled’ shortly before his death in 1886, and Louis Auguste’s fortune enabled Cezanne to provide for Hortense and the teenager Paul. But more importantly, it allowed Cezanne to get on with what he had to do: paint!

Cezanne was a voracious reader, and would have known of the attempt to introduce progressive taxation to counter the rising inequality within the young Republic (if only because of the possibility of his father’s inheritance being taxed!), but it received little consideration; an attempt to increase inheritance tax to a rather modest 1.5% had been flatly rejected by the National Assembly, invoking the natural right of direct descendants: “When a son succeeds his father, it is not strictly speaking a transmission of property that takes place; it is merely continued enjoyment of the property” (Piketty 141).

Anyway, it wasn’t Cezanne’s calling to address the inequalities arising within the young Republic; but it was worrying precisely because it seemed to be part and parcel of this new age; and though they had now all gone their separate ways – Cezanne and Zola, and the Impressionists, they all still longed for a new age that was not dominated by the Imperial, patriarchal and hierarchical traditions of the past, but that was colourful and natural, bright and open, free and equal.

Cezanne’s calling was to paint – and here in this place he was able to cherish what had been, and indeed celebrate it with an Impressionist painting!

For the future, he was confident that he could follow his creative spirit, wherever that would take him, for in some sense he now felt it was the creative spirit of a new age; but if it wasn’t, then hey, it’s just what he had to do!

In the randomness

of the way

the rocks

tumbled

my life

flows;

one of those gorgeous things

that was made to do

what it does

perfectly

After Mary Oliver